To Watch a Predator

by: Eric Freedman / Florida Atlantic University

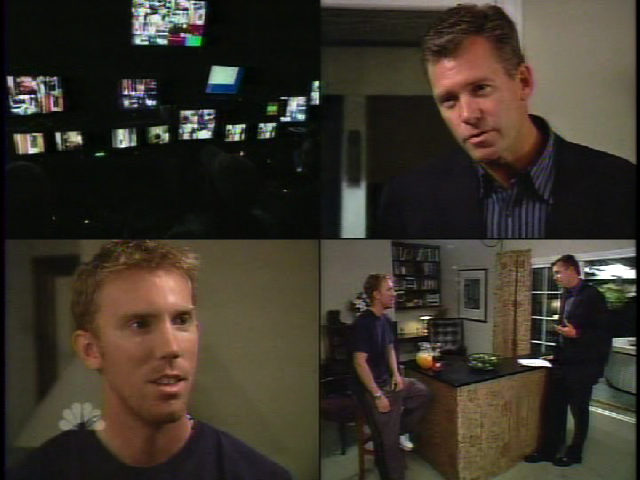

Views from outside a Dateline house

This essay is not a defense of pedophilia. But on Tuesday nights I find myself pondering the plight of reality television’s latest celebrities — men who are the unsuspecting players in Dateline: To Catch a Predator, investigative journalism’s response to America’s Most Wanted and Big Brother. Their broadcast debut is always framed by a dramatic dialogic volley between co-anchors Ann Curry and Stone Phillips. On the February 13, 2007 episode their exchange opened with the remark, “Some have seen it, now they’re on it, and our hidden cameras are all over it,” before moving on to the provocative fragment, “The teacher, the oil man, the ex-cop.” NBC’s Tuesday night lineup has become the occasional home of To Catch a Predator, which periodically joins the evening’s legal drama pairing of Law & Order: CI and Law & Order: SVU. First aired in November 2004 as a Dateline segment titled “Dangerous Web,” and with an undercover operation located in New York City, To Catch a Predator has since traveled to Washington, D.C., California, Ohio, Florida, Georgia, and Texas in the first ten installments of the investigative series.

My fascination with the series stems from the obvious questions associated with the network’s collaboration with law enforcement, and the common legal questions posed about this liaison. Are these participants the victims of a multilayered plan of entrapment that leads from chat room decoys, to hired actors, to correspondent Chris Hansen? Do these suspects have any right to privacy, or can they be freely featured as part of the flow of network television? In light of the serious nature of the potential offense (the victimization of children), these questions are often assumed to be irrelevant. Yet the show’s popularity, borne out by its ratings (Predator installments peak the Dateline viewership) and its entrance into popular discourse (parodied on YouTube and quite recently by Conan O’Brien at the Emmy Awards, and now in a stage of self-aggrandized historicizing with Chris Hansen’s recent book culled from his experiences on the series), makes an analysis all the more pressing. What are the cultural implications of a program that circulates information about an assumed public crisis?

Views from inside a Dateline house

In his discussion of epidemics — one form of crisis situation — Michel Foucault points out that the determination that a situation is epidemic is typically a political determination, one made by those with access to statistical data and the authority to make and circulate such determinations. Such an authoritative discourse governs NBC’s investigations of Internet predators, calling forth the dispensation of resources and the justification of tactics of surveillance and regulation as part of the broadcast serialization of pedophilia. Children are indeed being victimized, but the labeling of the situation as a crisis has depended upon the collection of data—tabulated and interpreted by “experts.” As part of this evidentiary process, visibility is simultaneously a problem and a solution. The show’s visibility has focused public concern on the crisis (in a sense bringing the crisis into existence by making it visible—though the program is certainly not responsible for the incidents themselves, and is only one flashpoint for its being called out) and allowed the authoritative discourse to take hold (made manifest in the mobilization of dollars and resources and the willful embrace of the network as protector of the public interest); indeed as part of this movement, citizens willingly surveil each other, and watch others being surveilled, perhaps part of the general neoliberalist spin down that once again turns the public interest over to private industry (consider, for example, the teen lingo cheat sheet on MSNBC.com, written to help parents understand the acronyms their kids use on the Web), and the unsurprising result of a neoconservative turn that gives information technologies significant leeway as tools of surveillance and discipline in the name of national security — “no privacy, no problem!”

From the Perverted Justice gift shop

Concern about the online exploitation of children has created a new growth industry of its own, with a complete line of products related to helping parents monitor the activity of their children. For its part, Dateline calls on the services of Perverted Justice, an organization that exposes men who sexually target minors online. Perverted Justice works as a consultant for Dateline (and is paid a fee for its services), setting up computer profiles and populating chat rooms with volunteers pretending to be underage teens interested in sex. The dystopic and utopic discourses about new technology converge in the Dateline narrative, as we are once alerted to the dangers of cyberspace yet told a tale in which technology is deployed as a productive social instrument. The paranoia of online identity as deceptive role play is displaced by the positive yet parallel action of the Perverted Justice decoy that plays a part to lure the predator. Predator and savior use parallel tactics that have evolved in tandem, and are positioned as the yin and yang of the digital age.

Correspondent Chris Hansen as author

With such a paradigm in mind, we are asked to accept surveillance as the principle raison d’être of certain new technologies, though in this climate the technology must be read as not politically or ideologically neutral. Reflecting on Predator’s development over its ten investigative installments, Hansen recalls, “The first investigation was very slick. I mean we had five or six cameras. And they set up a mini control room in like a little back room in the house. And they’re all huddled in there with the monitors.” Tracing the show’s development, one of the volunteers with Perverted Justice adds, “… We went from Frag [Dennis Kerr, the group’s Director of Operations] and I being perched on a single desk in a hallway at the top of the staircase—to having an entire room set aside where we’ve got our Web cams up, and we’ve got our phone verifiers in position. And we’ve got all these new technologies that we’re using. And Frag has gone from having a hallway window to look out of, to having something like 7 monitors pyramided around him.” The show is a testament to visibility, both in its guiding mission (to put faces on sexual predators) and its aesthetics of technological oversaturation. The undercover house in Long Beach, California, the set of its February 6, 2007 episode, featured fifteen hidden cameras, while the program itself split the viewing screen repeatedly, at one point offering home viewers four vantage points, plus those additional screens within the televised screen of the surveillance room.

NBC and MSNBC.com have expanded the Predator franchise to Catch an ID Thief and Catch a Con Man and package safety kits for each series. The Predator safety kit includes a family contract for online safety, culled from Safekids.com, asking parents to pledge, among other things, that they “not use a PC or the Internet as an electronic babysitter” and reminding kids to “be a good online citizen and not do anything that hurts other people or is against the law.”

Brian Massumi notes in his preface to The Politics of Everyday Fear, that “fear is a staple of popular culture and politics.” American social space has been saturated by mechanisms of fear production, a process perhaps hastened by the role mass media has come to assume in this country. Fear and the public sphere are illusive (and intimately bound to one another). But what Predator rather nonchalantly points out, as it produces “the teacher, the oil man, [and] the ex-cop,” is that fear is not simply outside the home, but down the hallway. These men are quite often (though not always) identified as family men, with wives and children. What public service is the network doing for their families? It is the very (virtual) nature of fear and of the public sphere that drives us toward empiricism, toward our need to know, to see, to find the sexual predators among us; yet what we may finally discover is that what we fear most is lying beside us.

Image Credits:

1. Dateline: To Catch a Predator aired 2-6-07

2. Dateline: To Catch a Predator episode aired 2-6-07

4. MSNBC

In a recent installment, Chris Hansen asks one subject, “Have you seen the show before?” “And what do you think of the stories?” “Did you ever think you’d be on one?”

Michel Foucault, The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception, trans. A. M. Sheridan Smith (New York: Vintage Books, 1973), 23.

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/17601568/

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/11030951/

Brian Massumi, “Preface,” in The Politics of Everyday Fear, ed. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993), vii.

Please feel free to comment.

It is not farfetched to think that the similarities between tracking down pedophiles versus the working of a full blown surveillance society are becoming increasingly difficult to make! It brings up the small difference between insanity and inspiration.

I wonder if NBC is using this franchise (To Catch a Predator, etc.) and these scare tactics to recoup viewers who fled the network and spend more time on-line now and away from NBC’s advertisers. This season, NBC ranks in 4th place among the 18-to-49 year old demographic.

It is interesting that NBC helped create a “safekit” that encourages parents (most likely 18-49) to “not use a PC or the Internet as an electronic babysitter.” Instead, Chris Hansen (and this ever-expanding franchise) would prefer it if parents used the television as the good old-fashioned babysitter – and inncreased NBC’s ad revenue, in return.

I actually saw part of this show once and some of the same thoughts came to mind as I was watching and not understanding why the featured “pedophile” did not even question NBC’s right to do this and his rights for privacy and “free speech” in some way i think also come into play.

So I just want to quote this sentence and comment on it: “The show is a testament to visibility, both in its guiding mission (to put faces on sexual predators) and its aesthetics of technological oversaturation.” I think that the ‘technological oversaturation’ starts with the way NBC and all the ones who are in charge of making this show, how they “induce” the situation to occur by setting the stage for “sexual predators” at every level: from cyberspace, to the stage ( house / meeting place), to the studio ( TV, the show). And due to the fact that the stage for this siutation was set in cyberspace, it then transfers to reality and visibility in the production of televison which then takes it back to virtuality (mainstream televison) and therefore plays with our fears. “Perverted Justice works as a consultant …setting up computer profiles and populating chat rooms with volunteers pretending to be underage teens interested in sex. ”

Not to defend pedophiles, but there is also a chance that perhaps all this men would not even become “pedophiles” in an envrionment where there were no Internet and cyberspace, and where there were no means for this men of connecting with kids or teenagers in a way which the Internet allows- basically, an unkown identity space for this kind of interaction to take place.