Watching TV Poker

a TV poker table

You may win, you may lose, but there’s always something you can learn.

— Former World Series of Poker Champion Greg Raymer, promoting pokerstars.net

The current moment seems an appropriate one for the much-hyped mainstreaming of poker as popular pastime, endorsed by the electronic embrace of TV and the Internet. Gambling and the risk society make a natural pair. Our president wants us to bet our social security pensions on the stock market while legal gambling has become a redevelopment tool of choice, state lotteries rake in regressive taxes, and casino gambling lies at the heart of the latest political lobbying scandal.

The trade-off of the zero-sum wager: vicarious pleasure in the prospect of a large payoff for the few in exchange for the willing sacrifices of the many fits neatly with the current administration’s fiscal policy, its western swagger, and its bluff-and-guts political tactics.

While the pundits continue to ponder the question of whether poker counts as a legitimate sport or not, there is a reasonable case to be made for situating it within the recent reality TV trend. It features the unscripted interactions of real people – some of whom were only recently recruited from the viewer ranks – along with the unfolding of (admittedly truncated) interpersonal dramas, and the promise that a lucky random fan might capture a piece of the multi-million dollar prize pool.

By way of contrast, football and baseball fans don’t, for the most part, watch the games for tips that might help them join the NFL. Poker shows, on the other hand, lay claim to the zeitgeist of interactivity by highlighting the participatory character of the revamped poker tours and offering how-to instructions sandwiched between advertisements for Internet sites where viewers can practice what they’ve learned.

As the publisher of one poker magazine put it, “One of the reasons why poker has become so popular is that anyone can be a poker player, anyone might be the next millionaire…I’m never going to play right field for the San Francisco Giants, but I might be one tournament away” (King, 2005).

A recent episode of the World Poker Tour cited the New York Times claim that some 50 million people in the US play poker regularly, and the televised tournaments are reportedly the third most watched “sport” on cable TV after car racing and football.

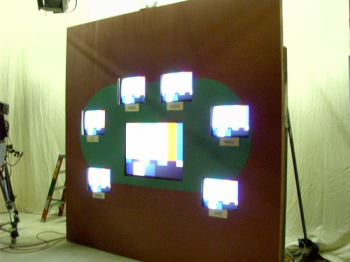

“Lipstick” Cam Monitors

The recent success of TV poker shows has been attributed to two developments: the “lipstick” spy-cams that provide behind-the-scenes access to players’ cards, and the proliferation of satellite games both online and off that offer amateurs and unknowns an inexpensive, long-shot bid for a tournament seat.

A recent episode of the Travel Channel’s World Poker Tour, for example, featured a segment about poker fans who parlayed their satellite buy-ins into lottery-sized cash prizes, prompting host Shana Hiatt to observe that, “Playing poker can be a dream come true for anyone.”

One of the staple narratives of the World Poker Tour is the back story of the amateur made good or the rags-to-riches pro. In this respect the show combines the appeal of big-prize game-docs like Survivor with the bootstrap narratives featured on celebrity reality shows like MTV’s Cribs.

Between edited segments of play, the World Poker Tour includes interview highlights with both amateurs and pro-players like Scotty Nguyen, a Vietnamese immigrant from an impoverished family who, as co-host Vince Van Patten put it, “went to help his family in the only way he knew how: he played poker in the street,” before coming to the United States and working his way up from busboy to poker pro with more than $2 million in winnings.

Poker shows hype the instant version of the American Dream even as its more prosaic version confronts the reality of increasing economic inequality and politicians hacking away at the social safety net. In this respect, the popularity of the spectacle of instant wealth continues the trend that saw the state lotteries work their way back into legality in the late 1960s and early 70s alongside the erosion of the post-war settlement and its attendant run of prosperity.

The current poker boom is also unmistakably a creature of its cultural moment – that of a generalized, reflexive savviness and a passion for debunkery that reduces every discursive claim to a ruse of power. The poker shows cater to the skepticism of those who seek to master the art of visceral literacy – ostensibly bypassing the manipulations of discourse to read the signs of the body. An instinctive “read” takes precedence over deliberation when everyone is assumed to be lying – and when the truth operates as one more ruse. The oft-repeated mantra that in poker “you play the people, not the cards” frames the commentators’ extemporaneous tutorials in mutual monitoring, detection and people-reading.

TV final table

As in the case of many reality formats, the poker shows promise to entertain the viewer while educating them. Home viewers are schooled in the art of “the tell.” Slamming your chips into the pot aggressively, for example, is a tell. Leaning back is a tell, as is leaning forward; a show of strength means weakness, and vice versa. As Celebrity Poker Showdown host Phil Gordon, put it, “looking directly at your opponent is a sign of weakness. You’re trying to look at your opponent to look strong; but if I have a good hand, why would I want to intimidate my opponent?”

The goal is to learn the significance of signals that are supposedly harder to control than words – to believe only your own eyes, never the other players’ words.

“This is a lesson for the players at home,” is the repeated refrain of the show’s hosts, who understand that the TV episodes double as advertising for a booming ancillary market in learn-to-play products, and for the tournaments whose jackpots increase in proportion to the number of participants they draw from the audience ranks.

The promise of participation in this context serves the opposite function of that associated with risk sharing. Rather than cushioning the effects of misfortune, it pools loss to generate a large payoff for those who finish “in the money.” Its alibi for regressive wealth redistribution is the democratic character of chance: the fact that no amount of skill or training can dictate the fall of the cards – and even the longest shot sometimes defies the most carefully calculated odds.

Despite this irreducible uncertainty (or perhaps because of it), the message is not the irrelevance of training and preparedness, but rather the need for their cultivation.

The credo of the well-tempered poker player, invoked by World Poker Tour co-host Mike Sexton is “In poker, as in life, you make your own breaks.”

The absence of any guarantee serves as incitement to ongoing training – and helps to displace an undermined faith in communication and risk sharing onto the blind justice of chance.

References:

King, Peter (2005) “Everyone’s a Player in Poker’s New Deal. The Los Angeles Times, July 17.

Image Credits:

1. TV Poker Table

2. “Lipstick” Cam Monitors

3. TV Final Table

It is a great article that i have read obove, I know theres a lot of people who are interisted on that kind of game though i know it is onother kind of gumbling and as we all know that gambling is bad and its agains to the law of government and in the law of God, but its up to us how to manage our self in this kind of thing, if we only want to enjoy our self then why cant we? As long as there’s no big amount include.

______________

delia

Highly relevant, efficient advertising to forum, blog, wiki and other types of web sites. Drive large number of visitors to your website and build quality links. http://www.widecircles.com

What a great post! I was looking for great articles like this for a long time. I bookmarked it! Thanks

This is why I signed up for this site: I don’t see stuff like this anyplace else .