Benny Hill and Reviving British Comedy

by: Anna McCarthy / New York University

Two weekends ago, BBC America aired a weekend-long Benny Hill Show marathon. The first few bars of the theme song, a farty sax novelty vaguely reminiscent of Spanish Flea, are enough to send Brits (and Americans) of a certain age into regressive infantile states. Grown men and women entered a thumbsucking trance as they gazed agog at the titillating but wholesome family television of the Olden Days.

What did hour upon hour of Benny Hill look like today? The racist excesses of the 1970s had to be removed, with characters like Chow Mein (a caricature more horrifying than its closest intertext: Mickey Rooney in Breakfast at Tiffany’s) airbrushed from history. But there was plenty of memorable, if repetitive, material left over. Musical numbers were preserved along with the skits, and viewers could enjoy once more the sight and sound of the Ladybirds crooning middle-of-the-road favorites in their jewel-toned caftans. And of course there is the sex. Buxom lassies dressed in hotpants and cowboy hats assaulted Hill’s lecherous old sidekick with their handbags. These same lassies joined up with other lovely young women for the iconic chase sequence that ends the show. Their prey is Benny Hill himself, who grins and winks as he scuttles down the High Street at accelerated frames per second.

Nostalgia aside, the current Benny Hill craze on BBC America can only mean one thing. Aunty is conducting market research to see if there is a U.S. audience for the in-production BBC biopic about Hill’s life and career. Written by Rumpole author John Mortimer, the film will focus on the doughy comedian’s problems with women. It will probably be unkind. In an interview with funny.co.uk, Mortimer characterized Hill as a miser who “died alone in this awful little flat and nobody realised he was dead until they smelt him.” These spiteful words reference Hill’s status as both a problem and a tragedy in popular narratives of British TV history. Although Hill was hardly the only comedian to objectify women or get laughs out of racial stereotypes in the 1960s, he is commonly characterized by certain types of aggrieved British folk as a man who was hounded out of television for being politically incorrect. In focusing on Hill’s inner demons, Mortimer’s script will likely try to address this issue by connecting the sexist treatment of women on the program to its star’s sexual hang ups. Troubling images will appear as the product of one man’s twisted psyche, rather than the systematic workings of a culture.

I do not mean to deny the deep human emotion that suffuses the best work of Benny Hill. The first time I ever cried at a song was when Hill’s number one recording Ernie aired on Top of the Pops in 1971. The song narrated the death of a West of England milkman in a duel with a baker over a woman; unfortunately, its status as parody was unrecognizable to a four year old, and indeed hearing it today brings a lump to my throat. But the significance of Benny Hill’s current TV revival goes further than one child’s personal developmental milestones. Rather, it is the “why Benny Hill, why now?” question that occupies me here. What do we make of this resurrection?

Coverage of the biopic on chortle.co.uk hints at one kind of answer. The site reports that Mortimer’s drama is airing as part of a series of film biographies of famous British comedians. This revivalist impulse will not only introduce the art and talent of a number of bygone comics to new audiences, it will also capitalize on the fact that, as happens every few years, British comedy is undergoing a perceived renaissance. Following on the success of The Office, the recurring character sketch program Little Britain has enjoyed phenomenal ratings and critical acclaim. The show aired with little fanfare on BBC America last year, but it appears on the schedule again this June and may attract more attention this time. (You can watch clips of it here.) Essentially, Little Britain parodies the representational conventions of BBC documentary programming and other quasi-governmental celebrations of the diversity of the British citizenry. Its depictions of average British folk are sharp-edged reuptakes of postwar myths of national character, rendered with an archness reminiscent of Paul Theroux’s scathing tone in The Kingdom By the Sea, his portrait of Thatcher-era Britain.

I mention Little Britain because rumor has it that Matt Lucas, one of the show’s creators, has signed on to play Benny Hill in the BBC biopic. It will surely be a pedagogical moment. Lucas will teach current U.K. viewers of Little Britain about the nation’s comedic past and how to think about it. In the U.S., his performance may convince viewers of BBC America that Little Britain is worth watching. More broadly, this juxtaposition of britcom generations will be instructive in its invitation to reflect on what has changed in British comedy over the years, and why.

In comparing Little Britain and The Benny Hill Show, It might be tempting to see the former’s satirical take on the didactic moralism of “a portrait of a nation” genres in British TV as an indication of greater sophistication. But when you watch a complete episode of Benny Hill from ages past it is surprising how much contemporary satire it contained. It may be that the lewd jokes are more enduring, but the programs that aired in the 1970s were chock full of parodies of news programs and other British-specific phenomena. What’s more — contrary to mainstream narratives of television’s increasing liberalization and/or censorship — comparing the two shows yields no evidence that British TV has become more “politically correct,” whatever that means, since Hill’s heyday. The ladies in negligees may be gone, but like most British comedy, Little Britain still trades on class antagonisms, in this case via the currently in vogue stereotype of class hatred, the so-called “chav.”

In fact, although it has been lauded for its innovative approach to comedy, there are plenty of continuities between the humor of Little Britain and the humor of the supposedly unenlightened past. When Lucas and co-creator David Walliams are asked about Little Britain‘s comic antecedents, they tend to refer to Monty Python and other staples of British collegiate humor. But the Lou and Andy sketch, one of the funniest recurring bits in Little Britain, is far more reminiscent of The Benny Hill Show at his best, both in its premise and its use of pantomime staging. Lampooning the cultural myth of the saintly invalid, the sketch depicts a wheelchair-bound man’s manipulative and deceitful activities behind the back of his naïve, long-suffering caregiver. And like Hill, the show recycles plenty of stock variety elements. There are men dressing up as women. There are mincing gays to laugh with or at. There are fast-talking displays of verbal skill and impersonation. There are sight gags and conventional types — the policeman, the burglar, the schoolteacher, the politician. And the same gags are recycled every week, much like Benny Hill.

So what do we learn from comparing Little Britain and The Benny Hill Show? I am still thinking about this, but preliminarily it seems that the comparison might annotate changes in strategies for rendering the absurdities of nationalism in satire, and translating these strategies across the Atlantic. One of the many bromides uttered by people in England when they talk about their comedy traditions is the idea that Americans “don’t get” English humor. American producers tend to agree, thinking that topical British humor is too subtle to travel across the Atlantic. Hence the remake phenomenon, documented in Albert Moran’s book Copycat TV, in which American producers translate programs like Steptoe and Son into American cultural idioms (Sanford and Son). But this strategy seems to work best with recognizable genres, like the sitcom. Satirical “copycats” have not been so successful. NBC’s recent attempt to make a version of The Office is only the latest in a series of disastrous remakes that stretches back at least as far as Max Headroom.

Not surprisingly, the parts of The Benny Hill Show that seem to have successfully translated are the broad humorous bits involving girls in negligees and men who are alternately lecherous or sex-panicked, not the spoofs of contemporaneous British TV shows and political events. Little Britain‘s satire, relying heavily on former Doctor Who Tom Baker’s delightfully pompous voiceover, suggests a different approach. Although it plays off culturally specific stereotypes, in the end the thing it is parodying — earnest depictions of citizenship and civic diversity — are recognizable as laughable moments of top-down national representation regardless of national context. There are of course elements particular to the U.K., like the rural Welsh accent of recurring character Daffyd — a portly homo-clubber who claims in the face of obvious counterevidence that he is “the only gay in the village.” But such humor ultimately rests on the incongruity of undermined assumptions about rural/urban differences, easily readable by an audience of American sophisticates.

My point is not to affirm cloying banalities about how “humor is universal” — difficult to do given Little Britain‘s clear identification with ways of mocking highly specific to British middle classes. It is rather to note with interest that the recycling of Benny Hill in the biopic relocates Hill in history, placing him in a lineage of knowing, ironic comedy stance that does not currently acknowledge him. Whether he will remain there is another matter.

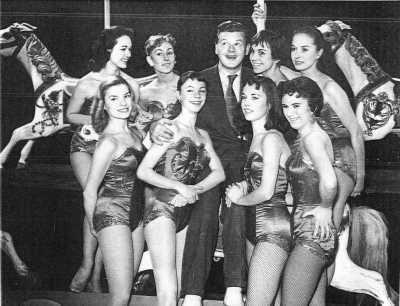

Image Credits:

1. Benny Hill Show

Please feel free to comment.

Pingback: FlowTV | This issue on Flow (10 June 2005)

British Comedies

I really enjoyed this article despite the fact that I missed this marathon. I think McCarthy’s placement of Benny Hill in history of comedy is an important step in thinking about who is left out of entertainment histories and why.

British Comedies

An interesting article. I think one interesting point might be who are the “American Sophisticates” and “where” they are expected to be found? In my viewing area, whereasBritish comedies are repackaged on the alphabet networks they are presented “as is” on PBS (which has a particular attitude to American comedicTV fare). This seems to speak volumes about America’s relationship with Britain and who are expected to “get it”. Thus whereas commercial network television is willing to be insulted by the English accent (Simon Cowell, You are the weakest Link Goodbye, a variety of Nanny programs and now Hells Kitchen)only a the PBS class can “get” British naughty humor.

Pingback: FlowTV | Flowers Powers: Mars or Venus?

Pingback: FlowTV | Reentry

tis just a complete shame … at the time it was ribald humour. and in the most part very clever humour.He just caught in the maelstrom of this p.c. world. do you imagine for one minute that young men are not going to be interested in young women: or that young women are not going to use young men to achieve thier own personal goals.. move the goal posts by all means. dress it up in which ever manner that you like. at the end of the day girls and boys. will continue in their own manner in spite of any rules and regulations… God rest Benny Hill Preserve his soul in death. He was a COMEDIAN…it was the evil cloud that killed him. One that continues to spread. It seems to me that Hiltler might have won his war after all. YOU ARE AN ACADEMIC= learned or scholarly but lacking in worldliness, common sense, or practicality.

Yes, Benny Hill, though deceased was racist. One of his shows depicted that the Chinese uttered some broken English syllables. There is no compassion for a foreigner learning another language with difficulty. What if the Chinese demands an Englishman to utter even half a sentence of fluent Mandarin (the Chinese language)? What if the French jeers at an Englishman who cannot utter any beautiful Paris intonation? What a shame ! Down with language chauvinism ! Down with racism !