Race and Reality…TV

by: L. S. Kim / University of California, Santa Cruz; UCLA

A prime-time line-up without reality television programming seems a lifetime ago. But it has only been three seasons since the last of the major broadcast networks added its first reality series. Just a few years of proliferation has splintered the form into subgenres, showering viewers with nightly lineups of alternate realities. But the more reality changes, the more it stays the same.

America’s historical love of self-help guidebooks and self-invention stories – the touchstones of the American Dream – have materialized in shows like Extreme Makeover, Extreme Makeover: Home Edition, Trading Spaces, Trading Spouses, Renovate My Family, and mentioning the unmentionable, The Swan. Horatio Alger tales are retold through as seemingly diverse fare as The Apprentice, American Idol, and even America’s Next Top Model. The trend began as contests of social politics leading to a cash prize (for the survivor of Survivor, one million dollars). New prizes include a job, a recording contract, a spouse. What the prize – and the moral of the story – really is, though, is personal transformation.

America’s Next Top Model logo

Personal transformation – whether from ugly duckling to “swan” or from poor country-bumpkin to rich, sophisticated entrepreneur – is integral to the grand American myths of race. It lies at the heart of how immigrants and their children are expected to assimilate. It also animates the expectations of those who believe in a “color-blind” approach to racial minorities, particularly African-Americans. It is telling, then, that reality television contains more characters of color than any other genre of primetime program. Furthermore, Reality TV is the only place in primetime where one can regularly watch integrated casts.

In stark contrast to the segregated nature of sitcoms, reality programs almost universally begin with a mixed cast of contestants. First, let’s deal with some terms here, like “contestant.” Certainly these shows are contests, but they are dramas, too. Stories are narrativized. Through the magic of editing, contestants are transformed into characters in what can best be described as an “ensemble cast.” The misnomer “reality” in “Reality TV” is a paper topic unto itself, but it suffices to say that from the viewer’s perspective, the participants on reality television programs are not mere contestants in a game show but well-developed characters in an unfolding story, rendered all the more dramatic by the fact that they are “real” people. The distinction is important. The color of a contestant on a classic game show like Wheel of Fortune may be irrelevant to the country’s racial discourse, for culturally-informed personality traits are of little import to the outcome of the game. Those traits are at the heart, however, of the social politics forming the contests on “reality shows.” Furthermore, producers shape our perception of these individuals. Editing, promo teasers, even the very unreality of the set-ups (e.g., fourteen beautiful women living together in a castle trying to woo a millionaire, or a man they think is a millionaire) mean that the personas we see depicted on our screens may or may not be accurate facsimiles of the contestants in real life.

Not only are characters of color present in reality television series, sometimes they even win. Vecepia Towery on Survivor: Marquesas, Jun Song on Big Brother 4, Ruben Studdard on American Idol, Harlemm Lee on Fame, and Dat Phan on Last Comic Standing are some recent examples. Winners are not determined objectively (another departure from the game show model), but by judges, by the voting television audience, or sometimes by fellow contestants, always based on subjective evaluations.

Indeed, the structure of the genre relies on the absence of objective standards of victory. For reality programs, the selection of the winner generally follows certain unspoken rules:

1) Show of Gratitude. A successful or compelling player must be grateful for the text, e.g., by praising and thanking the show (or God) for the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see his/her dreams come true. Those receiving makeovers must give heartfelt thanks to “the dream team” of doctors, dentists, trainers, and stylists for giving them (and by extension, their families) a new life. Bachelorettes must repeat their appreciation of the experience of being on the show and emphasize that they believe in “the process.” If you treat the show as a joke you won’t win, no matter how talented you are. You will be perceived as disrespectful. But of what, exactly? Reality TV? The audience? Or the myths that underlay the genre?

2) Sympathetic Back-Story. A Reality TV contestant may be popular, talented, and winsome, but s/he must have a good pre-existing story, one that follows a Horatio Alger and/or immigrant tale. Viewers love to see a rags-to-riches story, so if a contestant is poor, the odds are improved that s/he will make it past the preliminary rounds and into the finals. Both Ruben Studdard and Adrianne Curry lived in cars with their single mothers (in the South and Midwest, respectively) before becoming the dramatic winners (in Hollywood and New York City, respectively) on American Idol and America’s Next Top Model. On the other hand, “having it all” (intelligence, talent, good looks, and having been born into privilege) is almost inevitably a losing hand. Perhaps this is the most unreal aspect of Reality TV.

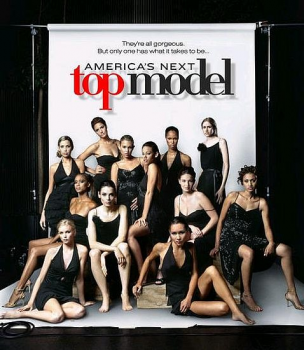

Top Models

3) Good Work Ethic. The winner of a reality television story must work hard. The opening theme song for Fame, a singing-dancing-acting talent contest, had the contestants sing: “We’re here to work-work-work!” Survivor contestants work and starve. Fear Factor contestants work and eat terrible things. Even if the work itself is contrived and meaningless, American viewers must see these people exerting energy and emotion in order to be worthy of becoming the winner or hero of a reality television text.

With these unspoken standards for achieving victory, Reality TV gives us heroes who uphold, reflect, and affirm core American values of equal opportunity for social and economic mobility in a democratic capitalist society through hard work, chutzpah, and a little talent, too. The talent may be the gift of being able to belt out a pop song, the skill to manipulate others to get them to achieve your aims, an ability to seduce a millionaire (bachelor) or impress a billionaire (bachelor) with your business acumen. Americans take comfort knowing (and seeing) that in Reality TVland, if not in real life, race is of no consequence with regard to possessing such skills and achieving such goals.

The very artifice of the “realities” created on the shows, together with the youthfulness of the genre, allow for multi-cultural casts that play out these myths. In contrast, from the birth of television, situation comedies have been set primarily within families, whether actual nuclear families or familial cohorts like Friends. The very structure of the sitcom genre was – and remains – inevitably segregated. Workplace dramas have offered greater opportunities for integrated casts and storylines, but the preponderance of police series risks the reinforcement of negative stereotypes of minorities. Because Reality TV is a relatively new invention (though of course it has its antecedents), Reality TV doesn’t have the same historical constraints and audience expectations of those other genres. In fact, notions of race and ethnicity actually play to the genre’s underpinnings – what better example can there be of self-reinvention with Gratitude, Backstory and Hard Work than that of a talented yet unthreatening member of a “model minority”?

William Hung on American Idol

Of course, not all reality series are alike and even the same program can be contradictory in its racial politics. While being open and possibly innovative in negotiating racial discourse, there are still racial tropes that capitulate to the lowest common denominator. Glaring examples include William Hung, the ‘Asian geek’ whose dance moves (and virginity) were exactly what we would expect them to be, or the derogatory character type of ‘the black –itch’ embodied (and edited!) so well in Omarosa.

But because Reality TV literally mixes up the usual television order-of-things, there is a bit more latitude in the ways in which characters of color can emerge. One can complain that the starting casts of reality shows seem too neatly to be “rainbow coalitions” of mere tokens, but there is no denying that in a largely segregated television universe, Reality TV proffers racially integrated casts. Mimi White brought up the idea of liking and disliking the same program at the same time. Likewise, can a viewer (and television scholar) praise and critique a television program or genre simultaneously? Admire its inclusiveness of race, class, gender, and sexual difference, but boo its conventional range of ideological values? I believe we can be both pessimistic and optimistic about television. This mode is in some ways, the very mode of television criticism. Reality television as hybridized and intertextual does not invoke simple viewing or simple pleasures, and it demonstrates that “getting real” (the tagline for The Real World) with racial difference is not such The Simple Life.

Links:

Home page for Fox’s The Swan

Home page for Fox’s American Idol

Home page for CBS’s Survivor

Home page for NBC’s Fear Factor

Image Credits:

1. America’s Next Top Model logo

2. Top Models

3. William Hung on American Idol

Please feel free to comment.

As an avid Reality TV watcher, I agree with Kim’s analysis, and I would like to add a few other thoughts to this discussion that relate to this type of entertainment in its current format. It is safe to say that a reality show is carefully planned, edited, and eventually aired in a way that it creates its own fiction. Little has changed since Kim posted this article, after all. Participants, whereas in a competition show or a docu-series, frequently tend to establish some sort of character or an identifiable personality trait that could easily describe them in just a few words: the sassy best friend, the pot-stirrer, the goody-two-shoes, the party animal, and so on.

Some shows, however, are notorious for going beyond “character creation,” and focus on plots instead. Bravo’s The Real Housewives franchise has become known to assign “story producers” to each cast member in order to help develop their storylines for the show. During a “Ask Me Anything” Q&A session held on Reddit, an anonymous production assistant stated these story producers “conspire to create plot points, image, etc…” and although they act as an ally to the housewives, “they are also in charge of creating exciting TV, and will influence their housewife to walk into setups.”

To some, this relationship might seem somehow one-sided, but it is in the housewife’s best interest to constantly bring an exciting storyline to the show. In past seasons, housewives who were deemed too boring were not asked back. One example of this situation was when Kim Fields, who is known for playing Regine Hunter on the ’90s sitcom Living Single, joined the cast of The Real Housewives of Atlanta (RHOA) for season eight, but struggle to create any kind of chemistry with the other ladies, to the point that during the reunion, the other housewives agreed she did not belong in the show. Needless to say, she was not asked back. On the other hand, infamous RHOA cast members like NeNe Leakes and Kim Zolciak both became extremely popular among viewers for their fiery personalities and constant feuding with each other and other members of the cast. They went on to get their own spinoffs and Leakes even participated in other reality shows (like The Apprentice, Dancing with the Stars, and Fashion Police) and on dramatized shows (Glee and The New Normal.) These two ladies, in particular, are constantly creating drama even when the cameras are not rolling and have tried on various occasions to distance themselves from RHOA, only to come back for other seasons. Zolciak recently claimed she will no longer make any appearances on the show but will continue to shoot for her own spinoff Don’t Be Tardy. Only time will tell if that is truly the case.

Another interesting aspect regarding RHOA is particular is its relation to race. When RHOA first aired in 2008 following the success of The Real Housewives of Orange County (RHOOC), it gained a lot of media attention for being the first cast made out of predominately African American women. As the first season aired, many critics complained the show depicted undesirable behavior, consequently promoting stereotypes and being a bad representation of black women. However, I do not remember reading anything similar about the ladies of RHOOC, although they arguably behaved in similar fashions: drinking (perhaps a bit too much,) spreading gossip, getting into yelling matches with other cast members, etc. It is interesting to see a show like RHOA both increase racial variety in television and also raise questions about stereotypes, especially since there are many other shows which are centered around the characterization of individuals.

Nice article

I´m sick of all these Top Model, Idol, German, American, UK whatever singstar, best dancer, baker, cook, whatever.

We love movies. Get the latest Hollywood and Latino news, movie posters, trailers, reviews, video, and movie giveaways such as free movie tickets.

Thank You For Sharing Wounderful Information! Great Work!

I read this article! I hope you will continue to have such articles to share with everyone! Thank you

Thank a lot For Sharing Wounderfull Information…

I´m sick of all these Top Model, Idol, German, American, UK whatever singstar, best dancer, baker, cook, whatever.